In 1991 I first played Another World (also known as Outer World and Out of This World in some regions), a game that would have a greater and more lasting impact on me than any other.

On the surface, it seems clear that Another World is a product of its time, and does not align well to some modern dominant design sensibilities. At the time though, it was pushing the envelope with its use of polygons and 'pixigons' and broke with many established motivational paradigms of the era, relying on a desire to explore and drive through the story rather than achieving a score or preserving lives.

In spite of its vintage, there are things that developer Éric Chahi was able to achieve in Another World that I believe are still relevant, enjoyable and worth aspiring to, even twenty one years after its release.

A piece of fan art based on the Another World logo.

- Atmosphere

- Characterisation

- Pacing

- Breaking Out Of Platforming

- Pushing Tech Boundaries

- The Journey Through Development

- Anniversary Editions

- Closing Thoughts

Atmosphere

Upon launching the game, the first thing that stands out is its atmosphere. Within the first moments of the intro cinematic, much of the game's tone is set, as the protagonist Lester (who is only named in the credits) is depicted arriving in his Italian sportscar at an isolated lab on a dark and brooding night. Lester immediately comes across as being successful, independent and yet lonely as he is greeted by the lab's AI and seats himself at a solitary workstation. The cinematic's score echoes this, playing an eerie isolated melody leading up to Lester's appearance, which is joined by a purposeful military percussion as he enters his workplace. As the experiment begins, rhythmic tensions builds before suddenly and unexpectedly, Lester and his desk are vapourised, leaving a charred crater with dissipating charge arcing across its surface.

The game itself begins with Lester and his desk materialising beneath the surface of a deep stone pool, a stark contrast to his technically advanced (and air filled) lab. The sense of displacement is real and highlights that Lester is no longer in an environment that he controls.

Another world has very little incidental music, using the intro cinematic to provide an initial sense of tone and pacing before giving way to sound effects. The first several scenes offer a full soundscape, with forlorn wind whistling through a rocky canyon, punctuated by seismic rumbles. All of the game's sound effects feel raw and visceral, adding to the game's air of danger and urgency. As the game progresses, ambient audio becomes more sparse, relying mostly on footfalls and laser fire to fill in the space. As a result of publisher pressure from Interplay[1], the SNES port (and derivatives) feature additional in-game tension music that deviates significantly from the style established in the cinematics. In addition to being out of place, I feel that this also detracts from some of the game's sense of loneliness and isolation.

In contrast to many other games of the era (Civilization, Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge, Lemmings, Street Fighter II and Sonic The Hedgehog, for example) Another World has a comparatively understated 16 colour palette with recurring dominant blue hues that help support its atmosphere of isolation and loneliness. Its muted tones depict not only an unforgiving and unmoving world (in which Lester with his red hair stands out), but also one that can be eerily beautiful.

"The real medium is the player's memory and imagination, so seeing once is enough to complete the mental picture of the game universe in his mind." - Éric Chahi, GDC 2011 Another World Postmortem

The game capitalises on its low-fi presentation, using implied detail over actual detail in a way that allows the player to project and interpret things rather than have them explicitly defined. It's difficult to know how much of this is a happy coincidence due to technical limitation of the time and how much was intentional minimalism, though there are a number of moments where the game gives the player fleeting glimpses of something separated from normal gameplay (using the short city view or black monster cutscenes as an example), enough to only give a sense or impression of what's shown.

↑return to top↑Characterisation

Lester is presented for the most part as a "silent protagonist", leaving his character open to player interpretation and projection. Beyond highlighting how out of place he is, the only definition the game gives Lester is when he is shown briefly emoting during his first encounter with members of the alien race (who presumably are indigenous to this planet, leaving Lester the real alien).

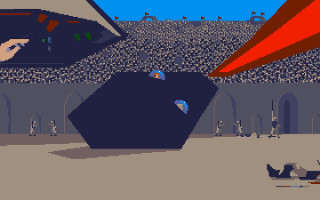

There's a degree of history and heritage to the indigenous people depicted within the game, who at once display aspects of technical advancement alongside cultural barbarity, with energy weapons and teleportation providing a stark counterpoint to the apparent slavery and bloodsports.

All three lines of dialogue are delivered in an alien language, two delivered by aggressive guards and one by the companion encountered by the player early in the game. This companion is shown to be amicable, caring and resourceful, and is undoubtedly the most developed character in Another World.

There's a degree of implied co-dependence that Lester and his companion share, and though Lester does not show direct response in game, the manual included with Another World contains a page from Lester's journal expressing concern.

"I am now separated from my companion in the escape, without whom I could certainly not have got away. I hope I will manage to find him and above all, I hope he is not dead, for I owe him my life." - Excerpt from Lester's Journal, Another World Amiga Manual

I'm yet to see someone play through the game without feeling a sense of connection to this character, empathy which I believe speaks to the success of Lester's "silent protagonist" role.

↑return to top↑Pacing

The pacing of Another World's gameplay is structured so as to heighten the impact of the game's tension centrepieces. The placement of encounters, obstacles and save points gives the sense that flow and pacing were heavily in mind as the game evolved.

As mentioned earlier, the game relies on players using trial and error (often resulting in death) to explore possibility space and discover solutions. For example, most players' first death will occur whilst they are absorbing the shock of Lester's transition from an air filled lab to beneath the surface of a murky pool. Invariably, all first time players I have observed are quickly pulled down into the depths by a mass of tentacles reaching from below. This first death introduces the notion that this new world (and the game itself) is not a friendly one, and that Lester's immediate task is to survive.

In modern context, this death oriented learning would be considered a negative aspect. At the time of release, the popularity of titles like Dragon's Lair and Sierra's line of adventure games, which heavily featured player death, made this much more accessible. To help make death feel less negative, many of these games employed special death animations or cutscenes as a reward. In particular the death messages/puns and animations in Sierra adventure are highly celebrated. Deaths with cutscenes in Another World are short and in line with the survival horror aesthetic, showing a glimpse of tightly framed jaws or claws in a way that implies the violent outcome without directly depicting it. Several types of deaths don't feature cutscenes and tend to be more graphic and bloody, though the zoomed out perspective gives them lesser impact.

Unlike Dragon's Lair however, each death in Another World (with the exception of combat encounters and platforming obstacles) provides a learning opportunity, and as such, technically isn't an end-state. This perspective feels to be an important aspect of finding Another World enjoyable and rewarding.

↑return to top↑Breaking Out Of Platforming

Two years before Another World's release, Jordan Mechner's Prince of Persia solidified what would be known as the "cinematic platformer", a style of platformer known for relatively realistic movement and more maturely constructed storytelling. Though Prince of Persia and Another World share some technical similarities, Chahi and Mechner were apparently[2] unaware of each other's work. Chahi mentions being inspired by Mechner's earlier work in Karateka, within which primitive versions of elements from Prince of Persia can be found, possibly accounting for some of these games' shared direction.

Unlike many other platformer games of the time, Another World features no in-game user interface, no scores, collectibles, limited lives or continues. Its player motivators have more in common with "point and click adventure" games (those being plot resolution and exploration), which may be the influence of Future Wars, the Delphine Software adventure title that Chahi had finished work on immediately prior to starting Another World's development.

Rather than relying on exposition, the story is delivered through Lester's actions. Unlike Prince of Persia, where levels consisted of movement challenges which were engaging, but did not expressly further the plot, every screen and encounter progresses Another World's narrative. This presentation of environment-and-action-as-narrative approach combined with a "silent protagonist" feels like a precursor to the kind of "ambient storytelling" that titles such as those in the Half-Life series (which often do also fall back on more traditional styles of exposition as a supplement) are celebrated for.

Beyond the progression of the plot, the player is guided by dangers and hazards to progress through the game in a way that positions Another World as being more of an observational survival game. With a few notable exceptions, the game presents players with all of the information they need at the time that they need it, and though a player may be able to intuitively work through its various challenges (providing that their reflexes and luck are working well together), it is expected that the player will die and die often in order to understand their situation and progress.

Another World's combat also stands out as being uncommon. Rather than collision damage oriented jump-on-the-enemy, button mashing or enemy weak spot mechanics, combat in Another World features zero-aiming gunplay. In addition, aggressors in the game carry identical weaponry (with the exception of rolling energy grenades) with the same abilities, putting them on an equal footing with player during combat encounters.

Whilst Lester can fire as fast as the player is able to press the action button, combat is regulated via a shield and a "plasma ball" mechanic that, when combined with Lester's ability to die from a single hit, leads to a more tactical experience. By holding down the action button for a short time, a shield can be created which will withstand a limited number of laser hits. Holding the action button for a long time will charge up a plasma ball, a powerful shot capable of destroying a shield in one hit. This manifests as a risk versus reward proposition that makes for an engaging experience that is not present in the weapon oriented already established "run and gun platformer" genre.

Also of note is the way in which player actions can be contextually based. Whilst the bulk of the game offers consistent walking, running and shooting behaviour, there are sequences where the presentation shifts and different movement or action mechanics are presented to the player. Even though it's used sparingly, this situational approach to control challenges the player's preconceived boundaries of gameplay and opens up a sense of possibility.

↑return to top↑Pushing Tech Boundaries

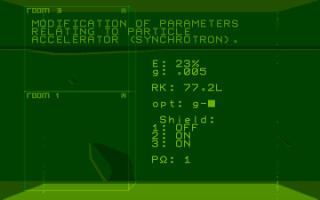

Inspired by the animation and cell shaded style of the Amiga version of Dragon's Lair, Chahi began to consider whether the storage footprint of such graphics could be reduced by rendering them as polygons and "pixigons" (a square polygon equating to a single pixel) instead of sprites. After prototyping a polygon renderer on the Atari ST as a proof of concept, Chahi went on to write an integrated development environment and runtime for the Amiga with a platform independent custom scripting language that allowed him to not only write the game logic itself, but also create and animate the game's vector graphics without having to recompile.

"Another World is basically an implementation of a virtual machine; if you fill in the details of this imaginary computer, the rest of the game just works, since the game itself is a program for this imaginary machine. This saved space, apparently, and it made things portable: you write an Amiga Imaginary Computer and you get Amiga Another World, you write an MS-DOS Imaginary Computer and you get MS-DOS Another World, etc."- Ryan C. Gordon

These early tech decisions which took up nearly half of the game's development had a huge impact on the game's portability, seeing it appear on over twenty five platforms since its original release, and the decision to create a tool for quickly creating and managing vector images and animations allowed for far faster production turnaround than a more traditional sprite based approach would have.

- The game logic should be coded in a language independent from all platforms, without needing compiling or data conversion. So I naturally orientated myself towards the creation of a script interpreter. I developed a mini-language structured in 64 independent execution channels and 256 variables.

- Polygon assembling: each visual display unit of the game was composed by many polygons, so it was essential to gather many polygons in one item, to facilitate their manipulation.

- Hierarchical structure of display: The polygon groups could be put together in turn to form another item. This hierarchical structure avoided redundancy through the creation of a priority system. For example, making a specific group for the head of the hero could be re-used in all phases of animation.

Taking a cue from more traditional animation, Chahi attempted to use rotoscoping to give Another World realistic animation. With access to a camcorder, getting source video of himself, a model car and the laser pistol (which appears to be crafted from cardboard and foam) was not a problem, but without modern video processing hardware and software, he was forced to improvise. Tracing frames onto cellophane from a paused image on a television screen proved to be too laborious for animation, and he eventually resorted to using an external genlock device and the Amiga's built in support for transparency which could then be composited with an external video source using an external genlock device. In spite of further technical challenges making the process awkward (which may have helped give some of the cutscenes the fast cutting and brevity that give them their impact), the workflow was manageable and Chahi was able to continue.

↑return to top↑The Journey Through Development

Rather than designing the game as a whole, Chahi employed a linear improvisational approach to development. With vector animation and rotoscoping representing the greatest technical unknowns, early development focused on making the intro cinematic work before moving on to level design and gameplay. In a short documentary created for the 15th Anniversary re-release of Another World, Chahi mentions that having a clear picture of the emotional experience he wanted to present to players allowed him to maintain consistency and pacing across development.

Chahi's own journey as he created Another World is in some ways reflected by the intense and draining journey that Lester is on. Working for the first time on a large scale solo project with new technologies and no clear direction can be a harrowing experience on its own, even before considering the isolating social implications of being a young game developer in the late 80s.

"It's true that there is a parallel with Lester's adventure, this character who is left on his own. He's on his own in a universe that is entirely unknown to him. There's a bit of a parallel with the creation of the game. Somewhere inside of me I had a feeling of loneliness. I unconsciously put it into the game. The extraterrestrial friend only increases this loneliness." - Éric Chahi, 15th Anniversary "Making Of" Documentary

With the amount of time invested in developing tools, when December of 1990 rolled around, Another World was only one third of the way through development. Along with the realisation that the project was taking longer than expected came mounting pressure and depression. In response, Chahi endeavoured to work faster, eventually looking for ways to optimise his production cycle through modular reusable resources and implementing support for raster background images that could be painted faster than vector backgrounds. During this stage in development, the story shifted to focus more on Lester's relationship with his companion, giving the game a cohesive thread that strengthened the narrative.

Chahi also began to approach publishers around this time as well, and after refusing one prospective publisher's requirement to reimagine the game as a "point and click adventure", he settled with Delphine Software, the French developer with whom he had previously worked.

By June of 1991, the game was still not yet finished, and no clear vision for how to wrap up the plot, Chahi fell back to storyboarding to define the scope and plot of the remainder of the game, putting aside his improvisational approach to explore possible conclusions before settling on the finished game's ending.

The limited timeframe of the targeted November 1991 release was so tight that Another World only received two playtesting sessions, leaving some balancing issues and other bugs in the initial release which would be fixed in later ports.

"At the end of development, I was exhausted, and this is probably the reason Lester was almost dying in the end." - Éric Chahi, GDC 2011 Another World Postmortem

Without the support of modern game developer communities, Chahi showed the same kind of resourcefulness, determination and enduring spirit in relative isolation - attributes that the player adopts when guiding Lester through his own journey.

↑return to top↑Anniversary Editions

The enhanced re-releases made for the 15th and 20th anniversaries of Another World's release attempt to make the game available to new and old audiences on modern platforms.

The ultimate long term benefit of Chahi's polygonal renderer was that the bulk of the game could be rendered at higher resolution without touching the assets. Similarly, the platform agnostic runtime and scripting language that the game was written in made porting to mobile devices, consoles, Windows, Mac OS and eventually Linux as easy as the initial Atari port.

"There's another benefit that no one was thinking about 20 years ago: if you have an imaginary machine that deals with rendering polygons, you don't have to map them to pixels in video RAM. Your imaginary machine can have a GPU do it at high resolution...and we do! With no changes to the original game. It's sort of wild."- Ryan C. Gordon

"For the Linux port of Another World, I didn't have to touch the virtual machine code at all. What was probably written in machine-specific assembly in the past, the newer versions of Another World have it in nice, portable C++. I didn't even have to look at the source code to that part; the effort was all in getting bits to the screen and speakers, and reading input devices."- Ryan C. Gordon

The re-releases offer the ability to use the game's original 320x200 resolution as well as higher resolutions. When rendered at higher resolution, new high resolution backgrounds are displayed. These new backgrounds were painted bitmaps rather than vector images and feature a larger colour palette to produce soft gradients to imply more shape and lighting.

Mouse over to compare the game's original artwork with that of the 20th Anniversary Edition.

These higher resolution backgrounds provide some really nice atmosphere, maintaining vector-like hard edges alongside their soft gradients. Unfortunately, their shading feels incongruent with the animated elements in the game (this stands out in the early prison scenes where the prisoners in cells have smoothly rendered depth whilst Lester's companion and the escapees in the foreground appear as flat vectors), and a small amount of the original background artwork's minimalism is lost. There is also at least one occurrence where the shading of a background does not match a vector element which is intended to blend with it.

For the 20th Anniversary Edition, a number of vector images and animations were tuned to improve positioning issues which weren't visible at the original resolution, though a number of these remain present (most notably, Lester's smile, clipping issues allowing ceiling tentacles to be visible whilst retracted into the roof, the dragon's wings, and even the pointiness of the pistol Lester finds). To perform this work, Chahi ran the twenty two year old tools he wrote during the game's development in an Amiga emulator.

The soundtrack and sound effects have also been given attention for the re-releases, with sound effects getting a remastering treatment and the intro and outro cutscene scores being recomposed and rendered with new samples.

The remastered sound is crisper, but diminishes the edginess of some of the samples. Others, such as the coughing[3] at the very beginning of the game feel slightly out of place compared to Lester's other vocalisations (with the exception of Lester's vine swinging shout, which can only be heard under certain conditions).

The new music is decently produced, though purists will likely prefer the original due to slight melody variations. Interestingly, the alignment of music, both new and old, against the game itself is subtly different in the re-releases to the original Amiga version. This makes some events during the intro and outro cutscenes feel less synchronised[4], though it is unlikely that somebody who hadn't played the original and specifically appreciated this would notice.

The cosmetic enhancements such as the higher resolution backgrounds and remastered sound effects togglable in the 20th (and 15th to an extent) Anniversary Editions, allowing them to offer an experience very close to the original or something that feels a little more modern. The experience is partially customisable, but not ideal in that the remastered audio can not be used without the new score, and the original backgrounds can not be used above the original 320x200 resolution (the latter presumably being a technical issue relating to the shortcut of creating some of the backgrounds as raster bitmaps during the game's original development[5]).

The 20th Anniversary Edition offers new "difficulty modes", which offer harder or easier experiences by adjusting enemy behaviour and density, as well as simplifying controls. The restructuring of save points for the MS DOS version carries through to the re-releases, making portions of the game easier to progress through. Whilst this was originally implemented as an improvement on top of the Amiga version, it does impact some of the pacing and flow of the game, putting the player in the middle of tension peaks when the game was initially designed to always give the player some lead-in.

In response to feedback on the original Amiga and Atari release's shortness, Chahi worked around the clock to create a new level which would appear in the MS DOS version and future ports. This level, which takes place between the corridor rescue and arena sequences is included in the re-releases and helps reinforce the relationship between Lester and his companion.

Whilst the characterisation value of this additional scene is undeniable, it feels less polished than the rest of the game. The grenade puzzle has far less direction than similar puzzles, and the chaotic gauntlet run does not do as good a job of communicating how and why deaths do or do not occur as, for example, the earlier corridor running sequence.

Another artifact from the MS DOS version is the lack of the crab-like creature that is visible walking amongst the leech-like creatures at the beginning of the game. Whilst this creature may have appeared to be cosmetic, it did suggest that the world in which Lester found himself was not intrinsicly hostile. The impact of this is definitely subtle, but it does allow for the expectation that not all active elements in the game will be threatening, something which I feel shifts the tone of the game in an important way.

Also included in the re-releases are a number of bonus items, including a copy of the remastered soundtrack, PDFs of design and technical notes, a piece of artwork, an 18 minute "Making of" documentary, and Amiga disk images containing the original release with copy protection functionality disabled[6].

The documentary is a short, but insightful reflective look at Another World by developer Éric Chahi, composer Jean-François Freitas and journalist Jacques Harbonn, giving a perspective on the memory of the game and its creation. A more intimate and time-subjective look at what was going on during development can be found in the technical and design notes, which include scans and images of concept sketches, puzzle design notes, artwork iteration, architecture notes, level codes and variable lists.

For me, the biggest treasure that the 20th Anniversary Edition provides is the Amiga disk images, which were not previously legally obtainable beyond picking up the limited existing copies second hand. Having the original release distributed in this fashion increases its longevity in an era where preservation of software is a low priority. The opportunity to play the game as originally created via emulation is nicely and respectfully provided (in comparison to 2013 remake of Flashback, which includes the original game presented picture-in-picture style in an arcade cabinet complete with a CRT effect despite never having been released as an arcade title).

↑return to top↑Closing Thoughts

It's difficult to distill the impressions I had over two decades ago as many of them have been overridden by subsequent experiences, but I do find myself appreciating things about Another World today that I never had considered back then. What I do recall specifically is that this was the first game that made me realise that a mature (from a technical perspective, not an age-appropriate one) and compelling story could be told through a game - all without one single word of spoken (human) dialogue. I remember being touched and moved in ways that no other game before (and very few games since) had done, and I remember being amazed and inspired.

Thrown into the (literal and figurative) deep end and expected to survive in a deadly world, the player's experiences parallel Lester's. Without a word of human dialogue, without direct exposition or emotive expression, players empathise with Lester on a level that allows them to share his implied personal experience. To feel his shock when attacked by the black beast, his urgency when fleeing from the barrage of super bolts, his panic when confronted with the alien cockpit dashboard, his dread and relief when falling and being caught, and perhaps most powerfully, the ambivalently comforting and isolating sense of companionship that Lester shares with a friend he can not talk to.

The critiques of the re-releases mentioned above are minor and are intended to highlight how high a standard the original game set, rather than to give reasons for avoiding the 20th Anniversary Edition, which does do the game justice (unless you feel that the game can not be played without the comical tension music from the SNES release).

↑return to top↑

A note from Cheese

Thanks for reading, and an extra special thanks to Ryan C. Gordon for his generosity[7] and enthusiasm for this game!

For some background on the Linux port, I first became aware of Ryan's interest in porting Another World when fellow porter Ethan Lee gave me a nudge. After one year of us chasing dead ends, full mailboxes and slow leads, Ryan was finally made contact with Abrial Da Costa, CEO of The Digital Lounge who was able to get things moving.

Although my contributions to this were very small (and ultimately I was not able to achieve anything directly), I'm really happy to have played a tiny role in bringing the game I love to the platform I use.

I am currently in the process of sourcing opinions for a follow up article, which will attempt to investigate the ways in which Another World has connected with fans. If you like this game, whether you're a long time player, or a new fan, I've put together a questionnaire to help encourage people to share their memories/feelings/stories, which can be found as a plain text gist on Github, or as a web form via Google Docs. I'd love to get as broad a response as possible, so if you know anybody who might be interested, please pass it on!

The keen eye will notice that Another World's sequel, Heart Of The Alien has gone without mention. Since Another World is what I was keen to focus on, it feels slightly out of scope for this article, and the much reviled sequel detracts from the experience and impact of the original. Chahi was also reluctant to see it happen, and left early in its development. He has since stated that he is not happy with the way it was handled. For those interested in learning more, Hardcore Gaming 101 has a detailed account in the second part of their feature on Another World (link below).

Another World is purchaseable for Linux, Mac and Windows on Steam, and it seems safe to assume that Linux support will be coming to other distribution platforms which support it in time as well.

For further reading, the following sites offer additional insight:

- The Official Another World Website

- Éric Chahi's 2011 GDC Talk

- Éric Chahi's 2011 GameCity6 Commentary

- Fabian Sanglard's Code Review

- Audun Sorlie's Hardcore Gaming 101 Feature

[1] Chahi faced additional pressure from Interplay who intended to change the intro and outro music in spite of his protests (which included wasting all of their paper with a neat 'infinite fax' with the message "keep the original intro music"), and eventually had to fall back on Delphine's lawyer to remind them that they could not legally exert creative influence over the game.

[2] According to Jordan Mechner's 2013 Reddit AMA, they met two years after Another World's release and became friends.

[3] In the original version, this occurs in time with the black beast hopping into view. It was always my impression that this was a vocalisation the creature made when spotting Lester.

[4] This synchronisation of music and image impacts on the way that elements presented on screen resonate. For example, in the intro when the security scanner recognising Lester, a melody and "military" style percussion enter, suggesting purpose and determination. Also within the intro are two moments where an alien sounding motif occur which feel distanced from the synthesised feel of the score, first as Lester's computer activates, and the second as he changes the opt value from g+ to g-. The latter suggests that this change may be responsible for the ensuing accident.

In the outro (spoiler alert), the initial forlorn melody is joined by an uplifting beat and baseline enters at the exact moment that Lester's companion appears, suggesting that his presence brings hope and some positive outcome to the end of Lester's journey.

The reduced impact of these moments feels like a great loss.

[5] I had considered attempting to make a mod for the 20th anniversary edition to accompany this article that replaced the new background images with more faithful re-creations of the originals, but the time investment was too large for me to commit to within the timeframe that I was aiming for. If anybody happens to be interested in working on or is already working on something like that, let me know about it.

I should also note that this doesn't indicate that I don't appreciate the new backgrounds (they're nice works, and even though one or two might lose a piece of detail that I liked, each one of them brings something worthwhile to the game's scenes). I just like the old ones ^_^

[6] The copy protection code entry screen still appears. Entering the same symbol repeatedly will allow the game to start.

[7] Ryan gave me one of 50 signed Another World 20th Anniversary Edition "retro" presskits, which were sent out on 1.44MB floppy disk complete with compressed Amiga disk images. I find it difficult to express how moved I am by this gesture.

If you've got any thoughts on this article, you can email me at cheese@twolofbees.com.

This article was first published on the 16th of September 2014.

Since you made it to the end, here's another piece of fan art I made whilst writing this article. You can find this and more over on Two Lof Bees

A piece of fan art based on a background character from the game.